Pride: One Volunteer’s Experience

“It was the war season.”

Topaz,* a sweet, giggly high school senior, all glasses and braces and dimples, had turned her computer screen to me and while I knew her assignment was to write a piece of fiction about a character who had gone, or was going, through a change in their life, I was NOT expecting she would kick off her story like this. But with just these five words, she had my complete and

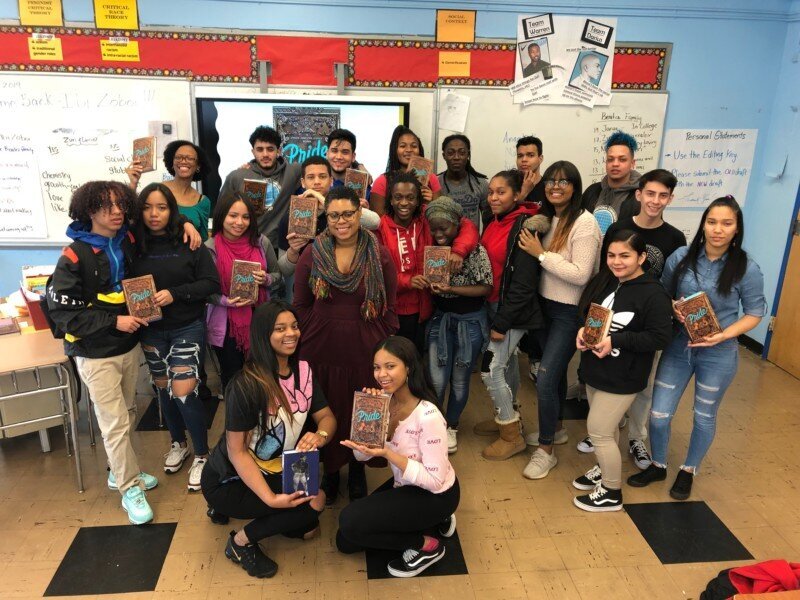

I recently spent a day with Topaz and other 12th graders at the International Community High School in the Bronx. Four sections of English classes had read Pride, by Ibi Zoboi, which is a retelling of Pride and Prejudice, now set in modern-day, rapidly gentrifying Bushwick, Brooklyn. The book is a delight whether you’re a fan of Jane Austen or not, and the ease with which Austen’s themes—of relationships and conflicts between class, family, love, death, religions, cultures, and more—translate to a modern novel only underscores the timelessness of these topics. But what really blew me away was how the ICHS students took up these themes and made them their own—how Topaz and her war season manage to be direct descendants of Austen.

First, a little background: The International Community High School enrolls exclusively students who are recent immigrants to the United States. According to the Department of Education, 85% of ICHS students are English language learners (compared to 12% city-wide). I’m going to throw a few more statistics out here, so bear with me: 28.9% of students at this school, or 126 young people, are in temporary housing, which is government-speak for effectively being homeless. That means more than one-quarter of these students, all recent immigrants, are in a shelter, on the street, or living with friends/relatives because they/their families cannot afford a place of their own to live. Nearly half of all students come from households living at or below the poverty line (for a family of four, this number was $25,100 in 2018) and 78% of students come from families eligible for some kind of assistance from the city. This means the ICHS has an economic need index of 98.2%, which is fully 26.9% higher than the city average. And yet? ICHS meets or exceeds five of the six metrics used to identify great schools and has a four-year graduation rate of 81.4%, which is six points higher than the city average. In short, ICHS is, as the DOE identifies it, a high-impact, but lower-performing school.

This may sound like a contradiction—how can a school be high impact but students lower-performing?—but just one day in an ICHS classroom will unpack that contradiction. The school itself has typical school energy—barely contained, brightly-colored chaos—and the walls are covered in messages and art and affirmations. There are posters about college everywhere and each teacher has her alma mater(s) on her door. The English teacher for our four sections was warm but firm and clearly in charge; her room was lovingly crowded with inspiration and ideas and tips and reminders. We volunteers had been made aware that some students might not have total mastery over the English language, but every kid—young person—I worked with seemed unself-conscious about this and resourceful. There was a cart with dictionaries of English to French, Vietnamese, Arabic, Spanish, Bengali, and Haitian-Creole, and I saw students asking friends for help in translating words— ¿cómo dice?, comment dit-on?, how do you say?—using Google translate, and sometimes writing in their native language, where they felt more comfortable, and then laboriously turning their story into English. The students were engaged and the atmosphere was warm and friendly and supportive and safe.

On the other side of the coin, I could not help but take note of how many of the student’s fictional stories centered around rape.

There were stories with bombs and guns and cheerful Topaz’ season of war. Mommadu, who had prominent scars on his hands and arms and neck and a clearly non-functional eye that was a startling light-blue against his dark skin, had a complicated story about a young man whose father abandons his family after which his mother turns to drugs and eventually dies, his brother is also killed, and the young man, alone, is raised up to be a hit man who is eventually given the job of assassinating his own father. Maria, who told me she was worried people would find her story boring, handed over two pages about a man with a rope tied around his neck, about to lynched for a rape he may not have committed. Santo was telling a story in alternating sections from past to present and present to past and his main character, the Tin Nutcracker, was a traumatized soldier who we see suffer through hellacious scenes of battle. Isabella had a story about a dancer who was injured when a stage collapsed and was trying to decide what came next: she had the scene of destruction and devastation down, but couldn’t figure out what happened after that.

A confession: a complicated thing for me about spending time in Behind the Book’s classrooms is figuring out how to be compassionate without being condescending, how to be encouraging and positive without being presumptuous, how to make sure I treat each student with attention to his/her circumstance without holding him or her to a different standard. This is why I am so grateful to writers including Ibi Zoboi who have crisply and with clear eyes taken the stories and the tropes and the themes that I grew up with and know well and shown me (and, hopefully, others) how those can live and breathe in other worlds, other cultures, other languages. In the end, what I have to remember is not how to navigate the differences between me and these students but to look for the similarities—to see the threads that run through all of our cloths, the truths we all universally acknowledge, in all the forms they can take.

As I talked with each student about how to push his or her work forward, asking questions and listening carefully to how these writers responded, I kept an eye on the others at my table. They were working together, pitching in with ideas and suggestions and English words and spelling corrections. They were kind to each other, they were cheerful, and even as they considered their narratives of war, of violence, of racism and discrimination and fear, they looked exactly like any other classroom of high school seniors, with their backpacks and their notebooks and their shared laughter and private whispers, Ernie and Jose conferring quietly while Nikki and Jeannie had their heads together, all of these bright young people with so much behind them, so much ahead of them, and here, now, today, for this one period of the day at least, in a safe and warm place to dream and imagine and create their own worlds where absolutely anything is possible.

by Casey Cornelius

*Students’ names are pseudonyms to protect their privacy.